ISSUE NO.7

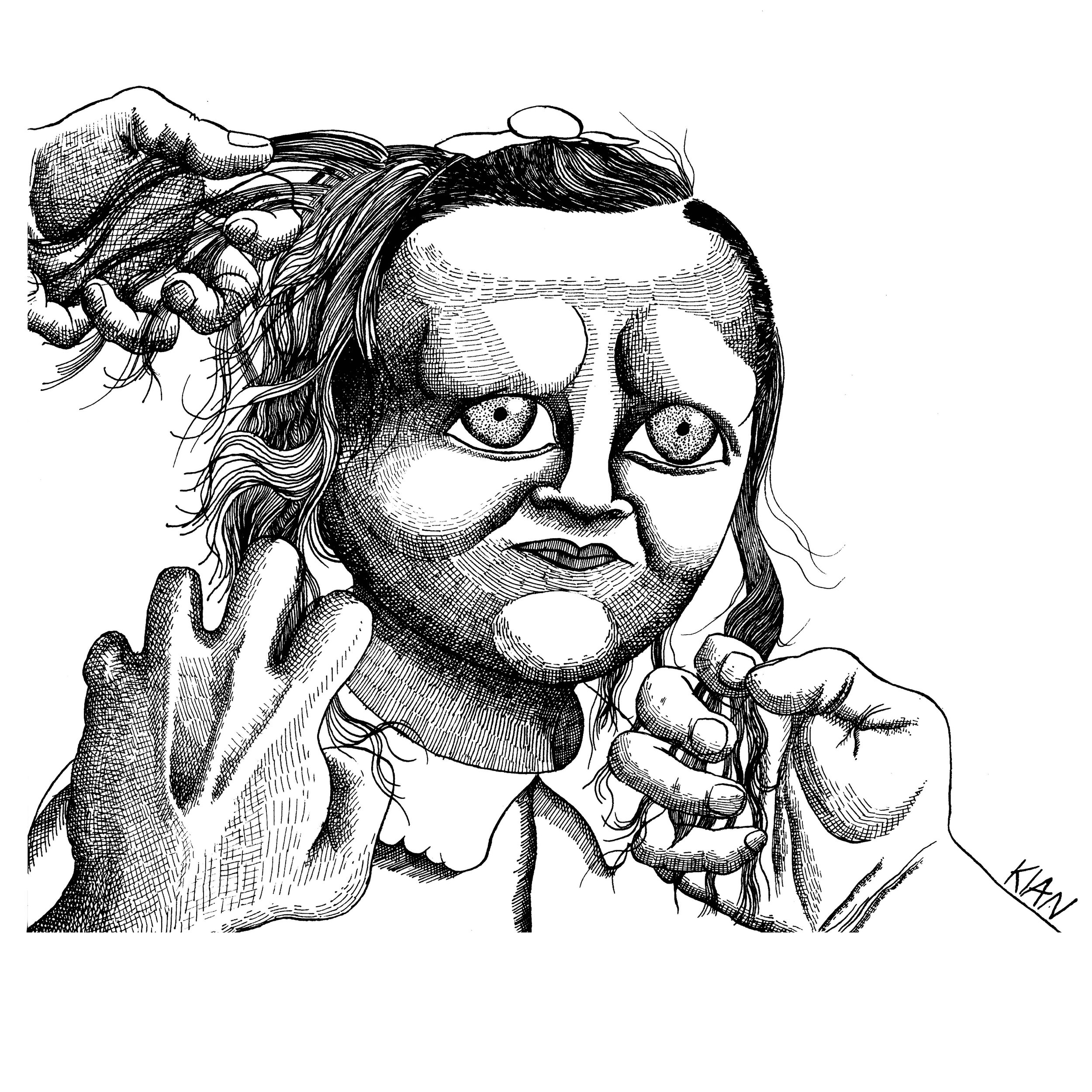

GIVE ME MY EFFING NOSE BACK

Aged seven, Anna Robinson found herself enrolled into the world of plaster-cast smiles, politeness-under-duress and “extorted gratitude” that accompany girlhood. Now grown, she questions how her outer boundaries became “semi-permeable”, longs to wriggle free from an embrace, to disallow access, to reclaim harsh lines.

April 7th 2023

Artwork by Kian Radpouyan @kian_radpouyan

59 St James’ Road: a semi-detached house in a string of Victorian three-beds. The back garden is on a hill, and in my memory it is forever doused in the scattered sunlight that sways through our Oak tree’s fingertips. There’s a rope swing; a silver tabby; two twin sunflowers planted by two twin children. Carved into the side of the hill are the garden steps - seemingly insurmountable concrete slabs that stretch from back door to back gate. I pretend to fall asleep almost every car journey so my dad will carry me over them,

against his shoulder.

The wall adjoining these steps partitions our semi-detached from number 57; it is enmeshed in thorns that bear blackberries every September. Absorbed in a cull of his portion of the brambles, our neighbour’s head lifts in and out of view. He is always in his garden. The sounds of his shears are entangled with the birdsong. He has white hair (it sprouts out of his head, nose and ears) and a red face. The adults call him ‘eccentric’. When he sees me he sings a friendly ‘hullo’. He takes off a glove, reaches a hand over the wall, and pinches my nose. “I’ve got yer nose, little lady!”

The nice man has been threatening to take my nose since we moved to St James’ Road. Fears of this olfactory crime occupy my thoughts, and I have a secret suspicion that one day I will wake up and find myself noseless, an empty cavern gaping back at me in the bathroom mirror.

I hate when he pinches my nose. But, age seven, I know that politeness is synonymous with compromise. I fear my discomfort will cause discomfort: ‘to create awkwardness is to be read as being awkward’, Sarah Ahmed warns in her essay on ‘Feminist Killjoys’. Already, age seven, I am beginning to master the technique of disguising my uneasiness. I fear reacting (overreacting); being perceived as impolite, or difficult. ‘Anything but the sunniest countenance’, Marilyn Frye observes, ‘exposes us to being perceived as mean, bitter, angry or dangerous’. So rather than batting the well-meaning hand away, I paint my expression in the hues of our sunshine garden, I feign a cooperative brightness. Then I retreat beneath the wall. Scurrying down those impossible concrete steps, a sandpapery ledge catches the back of my calf.

How often have I smiled to plaster over my discomfort when a situation, a remark, or a hand, strains over my outer limits? How did smaller surrenders of space lead to a lack of conviction in what was

mine to fight for?

‘Some bodies become blockage points’, Ahmed observes, ‘points where smooth communication stops’. Maintaining public comfort therefore ‘requires certain bodies ‘go along with it’’. It is easier (often safer) to smooth over your own unease - to replot those outer margins to avoid a collision with the interaction (maybe it’s the conversation; maybe it’s the hand on your back). What has been the compound effect of margins withdrawn, of inches given?

Maybe harsh lines and hard boundaries are irreconcilable with what we are taught about femininity : taking up space is conditional, permitted as long as we soften our edges. Politeness is a social territory that involves a constant forfeiture of space.

How did learning not to wriggle free from an embrace, unravel my ringlets from strangers’ fingers, or pull my cheeks from under someone’s pinch, inform a world where outer boundaries remain semi-permeable, semi-detached, overreachable - for politeness’, or smoothness’, sake. As well-meaning and affectionate as most of the small intrusions in these formative years were, they informed a problematic understanding of politeness - an understanding I now resent.Politeness is easily weaponised by those who are less well-meaning. A ‘compliment’ (the epithet often used to veil unsolicited and inappropriate remarks) might be deployed to enforce an interaction, rather than dispense straightforward kindness. It demands a response. A ‘compliment’ timed to when you are most vulnerable - walking home late, alone on the tube - is a threat. But politeness supposedly entitles them to engagement: a ‘thank you’, or a flicker of Frye’s ‘sunny countenance’. How powerless does that position of extorted gratitude feel? How sour does that ‘thank you’ feel on your tongue?

We moved from 59 St James’ road shortly after my eighth birthday. Our new garden, teetering on the edge of an isolated coast, was wildblown, salty, and detached. But still the sensation lingered - that uneasiness that I might always exist under a fate of half walls.